Two extraordinary fossils discovered by University of Leicester scientists are rewriting what we know about the lives—and deaths—of some of prehistory’s most fragile fliers.

In a new study published in Current Biology, researchers reveal that two hatchling pterosaurs, prehistoric flying reptiles, perished in violent tropical storms 150 million years ago. The very events that claimed their lives also created the perfect conditions for their remarkable preservation, offering rare insight into how these delicate animals entered the fossil record.

A Rare Glimpse Into Fragile Lives

The Mesozoic era, often dubbed the “age of reptiles,” is typically imagined as a world of giants—towering dinosaurs, enormous marine reptiles, and vast-winged pterosaurs. But, as lead author Rab Smyth of the University of Leicester explains, that image is misleading.

“Just like modern ecosystems, ancient ones were full of small animals,” Smyth said. “But because pterosaurs had incredibly lightweight skeletons—thin-walled and hollow for flight—they were extremely unlikely to fossilize. Finding not only a preserved specimen but one that shows how the animal died is vanishingly rare.”

That rarity makes the discovery of the two tiny pterosaurs, affectionately nicknamed Lucky and Lucky II, especially significant.

Death in the Storm

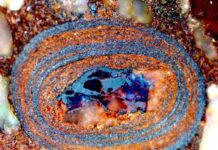

Both fossils belonged to Pterodactylus, the first pterosaur ever named by scientists. With wingspans of less than 20 centimeters (8 inches), they were only days or weeks old when they died. Their skeletons are almost perfectly intact—except for one striking detail.

Each fossil shows a clean fracture to the wing bone (the humerus): one on the left, the other on the right. The fractures were slanted, consistent with a powerful twisting force. Researchers believe these injuries were caused by sudden, violent gusts of wind during tropical storms, rather than by collision with hard surfaces.

Injured and unable to fly, the hatchlings would have been swept into the lagoon, where storm-driven waves drowned them. Rapid burial under fine limestone sediment then locked their fragile remains in time.

Solnhofen’s Secret

The fossils were unearthed in the Solnhofen Limestones of southern Germany—famous for exquisitely preserved Jurassic fossils, including Archaeopteryx. Yet Solnhofen has always posed a puzzle: hundreds of small, nearly perfect juvenile pterosaur fossils have been found there, but adult specimens are extremely rare and usually fragmentary.

The Leicester team believes their discovery helps resolve this mystery. Storms, they argue, disproportionately claimed inexperienced juveniles from nearby islands, sweeping them into the lagoon where they fossilized. Larger, stronger adults could withstand storms, and when they eventually died, their carcasses often floated and decayed before sinking, leaving only scattered remains behind.

“For centuries, scientists thought Solnhofen was dominated by small pterosaurs,” Smyth said. “But our findings show that this was an illusion created by the fossil record. Many of these juveniles weren’t lagoon dwellers at all—they were storm victims.”

A Window Into Prehistoric Storms

Beyond shedding light on pterosaur life histories, the study underscores how catastrophic events shape what we see in the fossil record. The tragedy of Lucky and Lucky II is also a rare scientific stroke of fortune, preserving a snapshot of ancient storms that raged 150 million years ago.