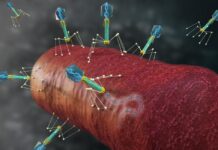

Imagine walking into your kitchen and forgetting why you came in, or struggling to recall a familiar friend’s name. For millions, these lapses are the first whispers of an aging brain. But scientists at UC San Francisco may have uncovered the culprit behind this slow fade: a single protein called FTL1.

Unlike the usual suspects blamed for memory loss, FTL1 seems to quietly tip the balance in the hippocampus—the brain’s memory hub. In studies with mice, researchers observed that older brains carried more FTL1, fewer connections between nerve cells, and weaker cognitive abilities. Essentially, the protein acts like a subtle saboteur, simplifying the intricate wiring that supports learning and recall.

When the team artificially raised FTL1 levels in young mice, their brains mirrored those of much older mice: neurons lost their branching complexity, and memory tests confirmed the decline. Conversely, dialing down FTL1 in older mice brought remarkable results. Neural connections flourished again, and the mice performed significantly better on cognitive tasks—a near-reversal of the aging process.

“This is more than slowing decline—it’s actually restoring function,” explained Dr. Saul Villeda, lead author and associate director at the UCSF Bakar Aging Research Institute. “It suggests the brain’s age-related vulnerabilities may be more malleable than we thought.”

FTL1 also seems to throttle metabolism within hippocampal cells, but stimulating these metabolic pathways counteracted the protein’s harmful effects. While human applications are still in the early stages, the research opens a tantalizing door: one day, therapies could target FTL1 to maintain or even rejuvenate memory as we age.

For now, the discovery highlights a simple truth: the aging brain isn’t a lost cause. By understanding the molecules that slow it down, science is beginning to show the way toward keeping our memories sharp—long past the years we might have once thought inevitable.