On a windswept Devon beach in 2015, what looked like an unremarkable stone turned out to hold a 242-million-year-old secret. Encased within the Helsby Sandstone was the delicate skeleton of a creature no longer than a finger — yet powerful enough to shake up what paleontologists thought they knew about the origins of lizards, snakes, and their ancient kin.

The species, now named Agriodontosaurus helsbypetrae, represents the most complete Triassic lepidosaur ever found in Britain. It predates dinosaurs by a few million years, and its discovery is forcing scientists to redraw the family tree of the world’s most diverse group of land vertebrates: the Lepidosauria.

A Surprise from the Sandstone

Lepidosaurs — today represented by more than 12,000 species of lizards and snakes plus the lone tuatara of New Zealand — owe much of their success to a flexible skull that lets them seize prey far larger than their heads. For years, paleontologists assumed their earliest relatives must have carried some of those defining features: hinged skulls, palate teeth, and a reduced cheek bone known as the lower temporal bar.

But Agriodontosaurus doesn’t play by those rules.

“This fossil shows almost none of what we expected,” said Dan Marke, paleontologist at the University of Bristol and the University of Edinburgh. “No hinged skull, no palate teeth. The only familiar trait is the open temporal bar. And yet, it has massive triangular teeth that set it apart from its relatives.”

A Predator in Miniature

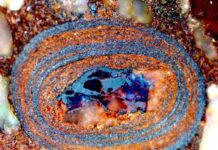

At just 10 centimeters long, Agriodontosaurus could sit in the palm of your hand. Its scans reveal large, blade-like teeth adapted not for swallowing big prey, but for piercing the tough exoskeletons of insects — a hunting style reminiscent of today’s tuatara.

“The detail is astonishing,” said Professor Michael Benton of the University of Bristol. “After careful preparation, we could see exactly how those teeth were shaped for slicing through insect cuticle. This was a small but effective predator.”

Older Than Expected

The fossil dates back 242 million years, in the Middle Triassic, making it older than Wirtembergia from Germany, previously the earliest known lepidosaur. That makes Agriodontosaurus the current record-holder for the earliest glimpse into the lineage that would explode into lizards and snakes.

Its unexpected blend of primitive and advanced traits is what excites scientists most. Rather than a neat progression from “archaic” to “modern,” early lepidosaurs may have experimented with a wider variety of body plans and diets than previously assumed.

Rethinking the Origins

For decades, textbooks suggested a simple path: ancient reptiles evolved skull hinges, lost certain bones, gained palate teeth — and voilà, the blueprint for lizards and snakes was set. But Agriodontosaurus throws that tidy model into disarray.

“This animal forces us to reconsider what features truly define the earliest lepidosaurs,” said Marke. “It doesn’t fit neatly into the categories we’ve drawn. It’s a reminder that evolution is messier, and more creative, than we sometimes imagine.”

A Fossil with Modern Echoes

Beyond the academic debate, this tiny skeleton offers a striking image of survival and adaptation. Its sharp teeth, its delicate frame, its role as an insect hunter in a lush, pre-dinosaur world — all point to how small creatures often carry the seeds of vast evolutionary success.

From the beaches of Devon, Agriodontosaurus helsbypetrae delivers a humbling message: the giants of prehistory may grab headlines, but it’s the small survivors that change the course of evolution.