In the quiet shadows of North American forests, a tiny invasion is underway. Most people walk past oak trees without a second glance, unaware that the galls—those peculiar, sometimes spiky growths dotting leaves and branches—are hosting a secret drama. Within these miniature fortresses, parasitic wasps are staking their claim, and scientists have just uncovered two previously unknown species quietly spreading across the continent.

Researchers from Binghamton University and collaborators across the U.S. traced these wasps, members of the Bootanomyia dorsalis group, back to Europe. Genetic analysis revealed two separate introductions: one along the Pacific coast and another on the East Coast, each likely arriving decades apart. The discovery, detailed in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research, not only uncovers hidden biodiversity but also raises urgent questions about the impact of invasive species on native ecosystems.

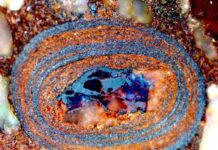

Unlike charismatic butterflies or beetles, these wasps are modest in size—mere millimeters long—but their influence is anything but small. They lay eggs inside oak gall wasps, the original gall-makers, eventually consuming them entirely. This predator-prey relationship is a delicate evolutionary dance, one that can ripple across local food webs.

“The more we look, the more we realize how much remains unseen,” said Binghamton University Associate Professor Kirsten Prior. “Parasitic wasps are incredibly diverse, and they play a vital role in regulating insect populations, yet we’re only beginning to understand their ecology.”

The European origins of these newly detected species provide clues to their journey. Some may have arrived with imported oak trees—English oak and Turkey oak have been planted widely in North America for centuries—while others might have hitchhiked on cargo, traveling undetected for weeks at a time. Once established, these wasps show remarkable adaptability, parasitizing multiple gall wasp species and spreading across regions from localized introductions.

The discovery underscores the importance of citizen science. Platforms like iNaturalist and projects such as Gall Week have allowed naturalists and students alike to document oak galls, helping researchers track the distribution of both gall wasps and their parasitoids. Without this collaborative effort, these stealthy invaders might have gone unnoticed for years.

Yet many questions remain. Do these wasps threaten native gall wasps or disrupt existing ecological balances? Could they affect other insect predators? As global change accelerates, understanding these dynamics becomes increasingly urgent. Scientists stress that these discoveries are more than academic curiosities—they’re a window into how ecosystems adapt, resist, or succumb to hidden pressures.

Parasitic wasps may be small, but their story is emblematic of a larger truth: the natural world is constantly in flux, full of unseen battles and quiet arrivals. In the gnarled nooks of North America’s oaks, evolution and invasion collide, and the outcomes may shape forests in ways we are only beginning to comprehend.