Imagine watching the impossible happen: from an empty space, tiny whirlpools suddenly spin into existence, as if conjured from thin air. That is precisely what physicists at the University of British Columbia have done—not with exotic machines or starship fantasies, but using a few atomic layers of superfluid helium cooled to near absolute zero.

The experiment mimics a long-theorized, never-observed phenomenon known as the Schwinger effect. Back in 1951, Julian Schwinger proposed that under extreme electric fields, the vacuum of space itself could produce pairs of particles and antiparticles out of nothing. The catch? The required fields were so intense that observing the effect in a lab was virtually impossible.

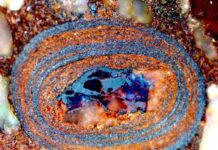

UBC researchers bypassed that roadblock by replacing the vacuum with superfluid helium-4. This frictionless, almost perfect fluid acts like a stand-in for space, and when set in motion, it spawns vortex pairs—tiny whirlpools spinning in opposite directions—spontaneously. “It’s like watching quantum turbulence come alive,” says Dr. Philip Stamp, the lead theorist behind the study. “Instead of electrons and positrons, we see vortices emerging from nothing. And it’s happening under conditions we can actually control.”

The breakthrough is more than a clever simulation. It challenges long-held assumptions about vortices, superfluids, and quantum tunneling. Previous models treated the mass of a vortex as constant, but Stamp and his colleague Michael Desrochers discovered it shifts dramatically as the vortex moves. That realization reshapes the way scientists understand the behavior of both superfluids and fundamental quantum processes that occur throughout the universe.

“These variations aren’t just theoretical quirks,” Desrochers notes. “They affect everything from how particles tunnel in quantum systems to the early evolution of cosmic structures.” In other words, tiny whirlpools in a helium film might hold clues to the physics behind black holes, the vacuum of deep space, and even the universe’s first moments.

Beyond cosmic analogies, the team emphasizes the practical potential of their findings. Superfluid helium is a real, manipulable system—meaning researchers can test predictions, measure vortex behavior, and explore phase transitions in two-dimensional systems with unprecedented precision. The laboratory becomes a window into phenomena that were previously accessible only in equations or imagination.

The UBC study not only opens doors to understanding elusive quantum events but also prompts a rethink of Schwinger’s century-old theory itself. The researchers suggest that the variable “mass” effect observed in helium vortices could apply to electron-positron pairs, subtly revising our understanding of how matter might emerge from pure vacuum.

For now, these tiny spirals in a superfluid film offer a glimpse of creation in action—a quiet spectacle where physics meets wonder, and where “nothing” may no longer be quite so empty.