Buried in the sediments of ancient oceans lies a forgotten record of Earth’s history — not written in stone tablets but in microscopic spheres of iron oxide. These tiny grains, known as ooids, have silently preserved a story of carbon in the seas stretching back more than a billion years. For the first time, researchers at ETH Zurich have decoded this natural archive, revealing that the oceans of the distant past contained far less dissolved organic carbon than scientists believed.

This discovery challenges long-held assumptions about how ice ages and the rise of complex life unfolded. Between 1,000 and 541 million years ago, a critical period in Earth’s history, the ocean’s store of organic carbon was as much as 99 percent lower than today’s levels. This overturns the prevailing idea that high carbon levels drove biological complexity and reshaped atmospheric oxygen at the time. Instead, the data suggest a more intricate interplay between life, oxygen, and carbon, driven in part by the emergence of larger organisms whose bodies sank quickly to the sea floor, locking away carbon in deep sediments.

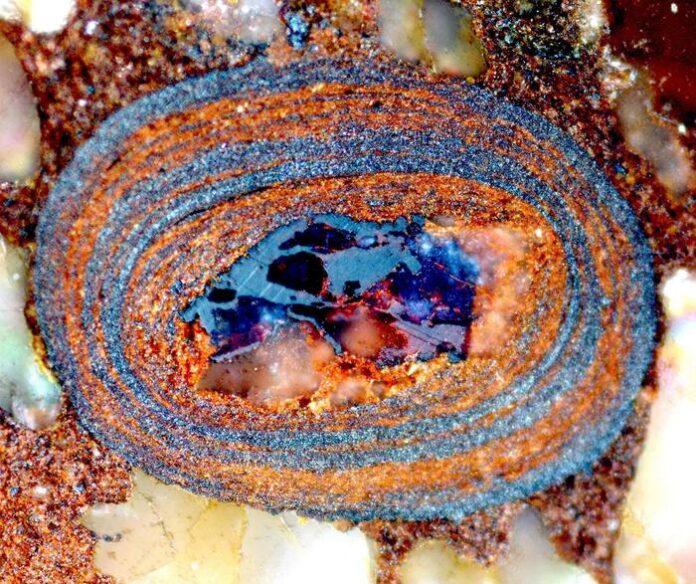

Professor Jordon Hemingway and his team have pioneered a method to read this hidden record by examining the organic impurities embedded in ooids. These “minute witnesses” — formed as layered spheres rolled along ancient seabeds — have retained the fingerprints of the primordial sea. Each layer holds clues about dissolved organic carbon, a vital component that serves as both a building block for life and a regulator of Earth’s climate system.

Their findings rewrite a chapter in Earth’s evolutionary story. The oxygen revolutions, long linked to life’s advance, now appear to have unfolded under conditions of far leaner carbon reserves than previously thought. It was only after the second oxygenation event that oceans regained their vast stores of dissolved organic carbon, paving the way for today’s thriving ecosystems.

The implications extend beyond deep time. As human activity warms oceans and reduces oxygen levels, the Earth may be edging toward conditions that mirror those ancient epochs. The lessons from these microscopic stones are stark: the ocean’s carbon reservoir is not a static archive, but a fragile system shaped by life itself. Understanding how it has changed before may prove crucial to predicting — and safeguarding — the future of life on our planet.