It sounds like a trick of science fiction: particles springing into existence out of thin air. For decades, the so-called Schwinger effect—where electron–positron pairs are expected to erupt from a vacuum under extreme electric fields—has existed only on chalkboards and in theory. The electric forces required are so enormous that no lab on Earth could ever summon them.

But researchers at the University of British Columbia believe they’ve cracked a way to mimic the effect without reaching for cosmic-scale power. Their laboratory stand-in? A film of superfluid helium just a few atoms thick.

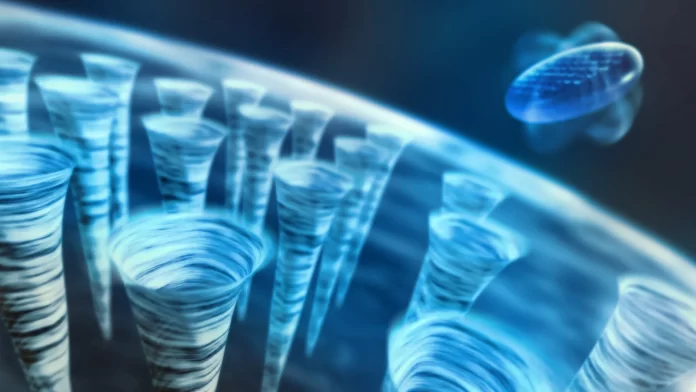

When cooled to near absolute zero, helium-4 enters a state with no viscosity, flowing like a perfect liquid. Under the right conditions, that flow behaves as a vacuum of sorts. Instead of conjuring particle–antiparticle pairs, it produces whirlpools of motion: vortex and anti-vortex twins, spiraling into existence from nothing and spinning off in opposite directions.

“It’s a kind of frictionless vacuum,” said physicist Philip Stamp, one of the study’s authors. “What you get are vortex pairs appearing spontaneously, just as electron–positron pairs would in a true vacuum.”

The findings, published this month in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, map out how the elusive Schwinger effect can be explored in a tangible medium. More than just an analogy for cosmic events, the work shifts how scientists view superfluids, vortices, and even the quantum rules governing phase transitions in two-dimensional systems.

For decades, researchers assumed the mass of a vortex in such systems remained constant. Stamp and colleague Michael Desrochers show instead that this mass varies dramatically as vortices move, changing the picture of how these entities behave in real time. That discovery alone could ripple into quantum mechanics, condensed matter physics, and beyond.

The implications stretch further still. If vortices in helium can reveal how mass changes in motion, the same principle might hold for electron–positron pairs in the original Schwinger theory, altering the foundations of how the vacuum itself is understood.

“It’s exciting to see how something we thought was fixed—like vortex mass—turns out to be dynamic,” Desrochers said. “It forces us to rethink tunneling processes that are central to physics, chemistry, even biology.”

The team emphasizes that the helium system is not merely a metaphor for the cosmos, but a real, testable environment with its own physics. Yet in its behavior, it also offers a glimpse into realms scientists can never probe directly: the quantum froth of deep space, the edges of black holes, perhaps even the earliest moments of the universe.

In other words, Calgary may have its dinosaur bones and Alberta its fossil beds, but in a UBC lab, a thin film of helium is letting physicists do something equally astonishing—watch “something from nothing” come to life.