Beneath the rolling coulees and quiet river valleys around Calgary lies a record of survival. Long before mammoths roamed the plains or bison thundered across grasslands, tiny creatures were carving out an existence in a world still reeling from catastrophe. Their traces remain, not in dramatic skeletons or towering bones, but in teeth—small, stubborn fragments that whisper the story of how mammals began to take the stage after the dinosaurs vanished.

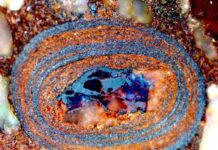

While Alberta’s fossil fame usually belongs to Drumheller’s badlands and the age of the dinosaurs, paleontologists say Calgary hides one of the richest archives of early mammal life. These remains date back to the Paleocene, roughly 66 million years ago, when the planet was recovering from the asteroid strike that ended the reign of the great reptiles. What thrived in that fragile new era were survivors: rodents, insect-eaters, and strange multituberculates—creatures that looked vaguely like rodents but carried bizarre blade-like teeth built for shearing plants.

“They were the quiet successors,” explained Dr. Emily Bamforth of the Philip J. Currie Museum. “Not large or flashy, but persistent. They represent the resilience of life after devastation.”

The fossil record around Calgary tells this story in fragments. Teeth and jaws of post-dinosaur mammals are scattered in riverbanks and deep cuts, testifying to a time when size meant vulnerability and only the small could endure. Over millions of years, some of these animals grew bolder. Dog-like carnivores appeared, along with ancestors of today’s hoofed mammals. By 38 million years ago, forests in southern Alberta were home to brontotheres—giant “thunder beasts” related to rhinos, creatures as large as elephants.

Though extinct, their echoes remain in modern species. Just as bison and mammoths later came to dominate, these early giants marked the first steps toward the mammal-dominated Earth we know today.

For scientists, Calgary’s mammal fossils are more than curiosities; they are data points in the planet’s survival record. By studying how small creatures endured after global disaster, researchers see parallels with the present. Environmental change, adaptation, and extinction are themes that recur in cycles.

“Paleontology is the medical history of the Earth,” Bamforth noted. “When we study how life rebounded after mass extinction, we’re not only looking backward. We’re asking how life—including our own—will respond to what’s happening now.”

In the end, Calgary’s overlooked fossils remind us of beginnings. The dinosaurs’ demise opened the door, and in the cracks of a broken world, mammals began their climb. What survives in stone today is proof that even after cataclysm, life finds a way forward.