On a clear evening, it can feel almost magical: a murmuration of starlings twisting across the sky, or a silver cloud of sardines darting in unison beneath the waves. No leader, no command center — just instinct and movement, perfectly coordinated. For decades, scientists have tried to unlock that secret, hoping to build artificial systems that can match nature’s effortless choreography.

Now, an international team of researchers says they’ve found a surprisingly simple answer — one rooted not in complex algorithms but in geometry itself.

The “curvity” principle

The scientists, including experts from New York University and Radboud University in the Netherlands, have introduced a new design rule they call “curvity.” Just as electric charges can be positive or negative, so too can curvity. This invisible property determines whether individual robots cluster tightly together or fan out into flowing flocks.

“Finding a geometric rule like this changes the game,” said Matan Yah Ben Zion, one of the study’s lead authors. “Nature achieves swarm intelligence without central control, and now we have a framework that points in the same direction for artificial systems.”

From birds to bots

Past efforts to mimic swarming have often relied on heavy computational control or centralized commands — approaches that limit agility and scalability. By contrast, the curvity model shows that simple mechanical design can drive collective behaviors without the need for constant oversight.

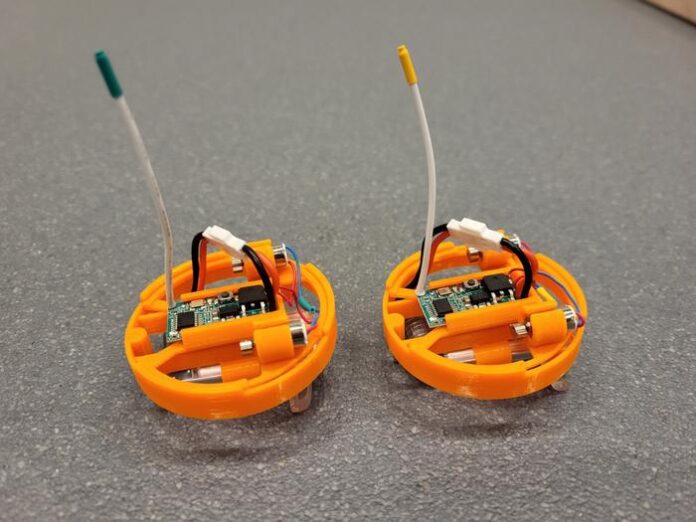

In experiments, researchers demonstrated that encoding curvity into small robots could dictate how they moved around each other — pairing up, clustering in groups, or flowing as a coordinated mass. The principle scales upward: the same rules that governed a pair of robots applied to thousands.

“It’s elegant because it’s basic physics,” explained NYU’s Mathias Casiulis. “You don’t need a supercomputer to make it work.”

Beyond the lab

The implications stretch far beyond academic curiosity. Swarm intelligence has long been touted as a future tool for disaster response, wildfire monitoring, or medical treatment. Drones working together without human micromanagement could scan vast areas in minutes. Microscopic robots could one day navigate the bloodstream to deliver drugs with surgical precision.

By reducing the challenge of swarming to a matter of material design, the researchers believe their framework could speed up real-world applications. “This could apply just as well to delivery robots as to micro-scale devices,” Ben Zion noted.

A shift in perspective

Rather than programming intelligence from the top down, the team reframes swarm control as a bottom-up exercise in material science. Each robot or particle carries its own rules, just as each bird or fish follows simple instincts. Out of those rules, complexity emerges.

That shift may be the breakthrough that has eluded artificial swarm research for years. As the study’s authors argue, simplicity — not complexity — may hold the key to matching the elegance of the natural world.