In a quiet lab in Dresden, Germany, scientists are revealing that evolution may not be driven solely by genes and natural selection—but also by the physical pressures that cells experience in the earliest moments of life. A new study in Nature uncovers how fruit fly embryos harness mechanical forces to guide their development, shedding light on how physical stress can shape evolutionary innovation.

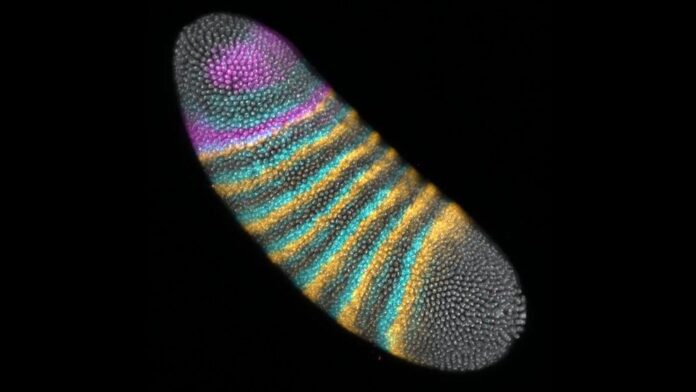

The focus of this research is a tiny structure in the developing fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) known as the cephalic furrow. Appearing as a subtle fold between the head and trunk of the embryo, the cephalic furrow may seem trivial. It doesn’t give rise to organs, and eventually, it disappears without a trace. Yet this ephemeral feature plays a crucial role: it acts as a mechanical stabilizer, absorbing the stress generated by rapid cell division and tissue movements during early development.

“Without the cephalic furrow, embryonic tissues become unstable,” explains Bruno C. Vellutini, postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG). “Cells buckle under compressive forces, and the embryo risks mechanical collapse.”

To understand how this tiny fold functions, researchers combined live imaging, genetic analysis, and computer simulations. They discovered that not just the presence, but the timing and position of the cephalic furrow are essential. When the fold forms too late or in the wrong location, its buffering effect diminishes, leaving tissues vulnerable to mechanical stress.

Interestingly, this mechanical function may explain why the cephalic furrow evolved in certain fly species. The intense forces at play during gastrulation—a transformative process turning a single-layered blastula into a multi-layered structure—likely created selective pressure for a structural innovation capable of absorbing stress. Essentially, the embryo engineered a solution to a physical problem, and evolution rewarded it.

Carl Modes, who led the theoretical modeling effort, emphasizes, “Our simulations show that a well-timed furrow acts as a mechanical shock absorber. The genetic program that creates it may have evolved specifically to manage these forces.”

The study also highlights the broader principle that physical forces can influence genetic evolution. Gene expression patterns, like that of buttonhead, correlate with the presence of the cephalic furrow across different species, suggesting that mechanical challenges can steer evolutionary change at the molecular level.

Parallel research led by Steffen Lemke and Yu-Chiun Wang found complementary strategies in flies that lack a cephalic furrow. These embryos deploy alternative mechanisms, such as out-of-plane cell divisions, to redistribute mechanical stress and prevent tissue buckling. Together, these findings paint a picture of embryos as active problem-solvers, using physical principles to navigate developmental challenges.

“This work shows that evolution isn’t just about survival of the fittest in the traditional sense,” Tomancak concludes. “It’s also about the survival of the structurally clever—organisms that can use physics to maintain stability and ensure proper development. Mechanical forces are not merely passive consequences of development; they are active agents of evolutionary innovation.”

As scientists continue to unravel the complex interplay between genes and mechanics, studies like these suggest a deeper understanding of evolution, one where physics and biology are inseparable partners shaping life from its earliest stages.